| Malaysia’s Hillstations - By Andrew Barber |

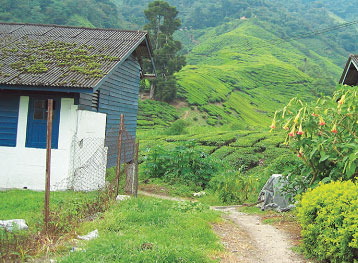

While most people associate the classic colonial hill-station with the British Raj and the famous Himalayan retreats of Simla, Assam and Darjeeling, Malaysia has the distinction of developing the world’s first hill-station - Penang Hill. It has also, arguably, developed the world’s most recent, the Genting Highland resort which was carved out of Pahang jungle in the late 1960s. First in and last out. Penang in the late eighteenth century was one of four “stations”, or Presidencies of the British East India Company (the forerunner to the colonial Raj) - the others were Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. Protected by a contingent of British officers and Indian sepoys and a Royal Navy docking facility at Georgetown, Penang quickly developed into a rich community of traders, missionaries, administrators and an eclectic cross-section of adventurers and camp followers from across Asia. Temptingly close to Georgetown lies Penang Hill. In the early nineteenth century the colonial settlers began to escape the enervating torpid climate of the coastal plain for the fresher air of the nearby forest and mountain. Access was by horse and by coolies bearing sedan-chairs up the steep mountain trails. Over time, bungalows (the name derives from low, airy single-story properties used by the East Indian Company in Bengal) spread across the upper slopes of Penang Hill - and the world had its first hill-station. True to the rigid colonial social hierarchy, the settlement was not without rules. The Governor’s bungalow, Bel Retiro, perched at the top of the hill from where it prominently flew the flag (hence the alternative name, Bukit Bendera or Flag Hill). Penang Hill received a major boost when, in 1923 and at a cost of US$1.5 million, a funicular railway was built. During these years, with high profits from tin and rubber, planters and miners built their own retreats, though, given their association with trade (the British had an ambiguous relationship with commerce – they liked its money but looked down on its protagonists) their houses were down the slope from the administrative elite. The vastly richer Penang Chinese traders, the towkays, whose elaborate mansions were gracing Gurney Drive, built their own retreats; while far more opulent than their British counterparts, in line with the colonial pecking order, these were even further down the hill. In the late nineteenth and into the twentieth century, in step with the colonial development of Malaya, a set of hill-stations was established along its mountainous jungle spine. Fraser’s Hill near Kuala Lumpur; Maxwell Hill behind Taiping and the Cameron Highlands were all developed as hill-station resorts for the British community. The process was not an easy one, as virgin jungle had to be cleared and expensive mountain roads constructed. In some cases, such as in the Cameron Highlands, the driving force was the vision of opening up the temperate, rich agricultural possibilities for tea plantations and market gardens, with the resort following in its wake. The hill-station “resorts” promoted therapeutic and health-enhancing qualities. In an era before air-conditioning, and with duty tours lasting many years, the escape to cooler air must have been most welcome. But the stations also played an important role in cementing, consolidating and sustaining colonial society. Unlike today’s expatriate community, with its focus on the big cities and with relatively few expats living in the smaller towns and rural areas, the colonial population was spread wide and thin. Many tin miners and planters led isolated lives. Particularly for women, with children at boarding school in Britain, it could be a lonely and testing existence. The retreat to the hill-station for holiday and “leave” was as much mental as physical therapy, and this may explain why it became such a totem of colonial life; an “escape” from the often far from idyllic world of plantations and isolated homesteads to a community. The British attempted through the hill-station to recreate a tropical version of “home”. Whatever their origins in Britain (few were from wealthy, landed backgrounds) in the hill-station the colonial residents stayed richly in “rural” stone cottages with fireplaces and hearths, a pastiche of the rural idyll of Olde England. The hill stations, albeit buttressed by a small army of servants, permitted an exclusive European social environment. They were detached and isolated from the realities of colonial Malaya but had complexities of their own; strict rules of hierarchy and the intricate social norms of the class and race-conscious colonial British. In letters home and in memoirs, however, the recollections of holidays in hill-stations are invariably positive. For leisure, there was golf, riding, tennis, walking and the pleasures of well-stocked gardens. Bridge, amateur dramatics, tea parties, picnics, dinners and luncheons were the fare that kept the hill stations alive. Today, some of the hill-stations are somewhat marred by ugly developments but a visit remains an enjoyable and relaxing experience – either for a weekend in the Cameron Highlands or a drive and lunch at Fraser’s Hill. The hill-stations are now, of course, enjoyed by all, but the introverted world of the colonial community can still be glimpsed in the older buildings, with names like “Rose Cottage”, each little fictions of England with views stretching out over Pahang’s endless forests.

|